END

by Barbara on Jun.16, 2009, under Published Novels and Short Stories

END – A NOVEL BY BARBARA ADAIR

Shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, Africa Region – 2008

SUMMARY

In this new novel from Barbara Adair, End, the reader is transported to the Johannesburg and Maputo of the 1980’s; where wars of varying violences erupt and conjure the edgy, war-torn world of the film Casablanca. Adair’s writing is brutally funny, witty and unnervingly erotic. This novel breaks new ground in the relatively unexplored territory of the South African post-modern novel, where the characters talk to the narrator about their uncertain destiny. JACANA MEDIA

The First Chapter

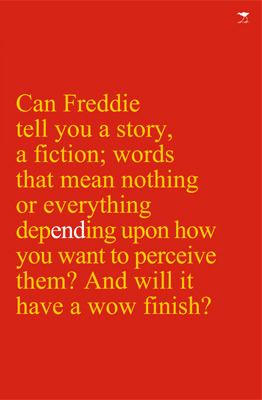

Can Freddie tell you a story, a fiction; words that mean nothing or everything depending upon how you want to perceive them? And will it have a wow finish? ‘Hey Mister, I met a man once when I was a kid.’

The last time he saw X was in the Caminho de Ferro City railway station, the train station in Maputo. Around them people ran back and forth. A hectic fevered excitement seemed to have overcome all of those who wanted to get out of the city. He remembered that they said goodbye under the large clock that was on Platform 15. Platform 15 was the only platform that was working in the station and the trains snaked along it, creeping and crawling. The other platforms just consisted of tracks, lonely untrained tracks. He thought for a minute, what did it remind him of? Then Freddie reminded him, she whispered in his ear, ‘Casablanca; that scene when Rick is waiting for Ilsa at the station in Paris.’

Ah yes, he remembered it now. It is pouring with rain, the black and white raindrops bouncing off Rick’s grey fedora and onto his face. He stands under the clock on the platform, looking constantly at his watch and waiting for her. A lone man amidst a crowd of people. He reaches his hand up and touches his head. His hair is dry.

It was not raining in Maputo. And he did not wear a hat. ‘This reminds me of that scene in the movie Casablanca,’ he said to X.

‘What scene?’ X asked. ‘I remember seeing it, but it was so long ago.’

‘It’s that scene on the station platform in Paris. It’s raining and Rick is waiting for Ilsa. They are leaving Paris to escape the Nazis, but she does not arrive…’

‘I’ve had a lovely time these last few days,’ X interrupted him. ‘I can’t stay with you now… Don’t ask me why. I wish I could. Go now, my sweet darling boy. Remember to send me the photographs… You used black and white film didn’t you? They should be good.’ As he held X’s hand he said the name to himself, X. X can’t even understand this, he thought, this clock on the platform, and the fact that we are standing below it to say goodbye.

Freddie looked at him, jealously, watching as if through the slats of a window. He was so far away. ‘Can I hold your hand now?’ she said to him. But he did not reply, he just sighed and held X’s hand more tightly. He felt that if he let the hand go he would never hold it again, and he did not want to let it go. If he let go the hand it would be gone forever. The image of Rick was still in his mind.

‘Thanks Freddie, for reminding me of the movie,’ he said. ‘It has made things so much more complicated; now I will have to think about love and romance… love and loss.’

‘No you won’t,’ Freddie replied. ‘I’ll have to deal with the clichés. After all, I’m the writer, the author. I’m writing this story. I’m the genuine creator. And if Martin Amis can do it in London Fields, well I can too. Wait for me. I’ll walk down streets I’ve never been to. I’ll meet characters I know I’ll never know. I might even fly away.’ Freddie turned to him. ‘Do you think this is an unoriginal style?’ But she didn’t wait for him to reply. ‘Is there anything that is original? Some writers just do unoriginality better than others.’

It was Maputo, not Paris, so it was not raining. The waning sun shone down margarine yellow. It clung wet garment-like on the walls of the monolithic station and draped itself over the arching roof. It was hot even though the sun was already setting. The station was outdated now; European architecture with Art Deco mosaics decorating the walls, a peppermint green design that was going slightly mouldy. Everything in Maputo had that slightly aged look. The ever-present Portuguese, now old and dying, had, as something new, adolescent, tried to become adult. The death of the Portuguese in Africa. The building reminded him of the fascist architecture in Europe, the station in Milan, Mussolini’s last stand, Mussolini’s mausoleum. Everything reeked of death in the station that night; his breath like the dying embers of a fire, the scrawny chicken that was going home for supper, the robust ticket seller who demanded 100 Meticais over and above the ticket price for a seat in first class. And first class was empty anyway. Death and darkness. He knew it would be dark when he eventually left the station, dark and hot. The sultry tropical air would embrace him, much like X had embraced him in those white sheets. Those white shrouds.

‘It must have been passionate for you to come up with this death and dying description,’ Freddie said to him as she felt the feel of the city and read the words. ‘But you’re not the first to think of death and sex together, sex and murder… The Marquis de Sade…’ But who was passionate, he or she, or maybe just the Marquis?

He continued to speculate without thinking of Freddie. Strange how they said goodbye under that clock. Rick was leaving Paris to the Nazis and he left alone. He was leaving X in a beautiful fascist building, and X was returning to London. And he would be left alone. He kissed X on the mouth. For a moment he thought that he just might love X if he got the chance. Would Freddie give him the chance, he wondered. Michael Curtis gave Rick and Ilsa that chance and what happened? They were immortalised in black and white close up shots. Maybe he would get a chance this time, maybe this time.

‘You’re already immortal. Words don’t die. They just have to be read. It’s only the readers that die,’ Freddie said to him. Simultaneously Freddie thought, Fuck, now I have the archetypal lone hero on my hands who doesn’t want to be the lone hero. What other lone heroes can I use as a model to describe him? Did they all want to be heroes? Did they want to be heroes at all? Or do all of us, the reading public, make ordinary people doing ordinary things into heroes – commodities? She thought for a minute. Oh well, what does it matter? Che’s bloodied and tortured body lying on the Bolivian planks in the barracks, alone in a postcard. Rick, where I’m going you can’t follow. What I’ve got to do you can’t be any part of. I’m no good at being noble, but… which ones didn’t fulfil the cliché, or did they all fulfil it?

A whistle blew. ‘It’s the last call, X. The train will soon leave,’ he said. X climbed aboard the train. He handed him what was left of a burnt out cigarette. He thought he heard X say, ‘Here’s looking at you, Kid,’ but he must have been mistaken, for X had never looked at him, looked into him.

And, Freddie reminded him, ‘X doesn’t even know that he’s in a movie, so how would he know what words to say?’

And then X was gone, up and into the train. He turned and walked along the platform. He put the burning ember between his lips, his full lips. His mouth drank in the smoky air. The coal glowed, but only for a moment. Then the smoke curled above his head. It filled him. He crushed the butt out on the sole of his shoe and threw it into a nearby dustbin. He never did look back to see if X waved to him from the open window of the carriage. Rick never looked back, so why should he? And when Freddie looked back she saw that X did not wave from the open window.

As he walked back down the Avenida Patrice Lumumba he felt the tears from behind his eyelids drip down his checks. He turned to look in a shop window and his reflection looked back out at him. For a moment he thought he saw a mark, a scar on his forehead, a bullet wound. But then as he moved he saw that it was only a shadow cast by a curved and bent lamppost. There was no wound after all. Only a few tears, and those he knew would soon be gone, dried by the slight breeze that blew up from the sea. Forgotten as he went about his life. Forgotten like the people after whom the streets were named, a city of dead and dying heroes. The dirt of his grave was already sprinkled on his face.

He wondered if he really should be thinking of X as he walked down this street. How inconsequential their little interlude must seem in the vast space of history. As he walked he wondered if he truly was the deep thinking philosophical type, and if so, if he would really be thinking in these images, in this way? Sex was on his mind. But then, he rationalised to himself, maybe it was Freddie who had sex on her mind, not him.

And then, as if she could read his mind – well she could read his mind – she interrupted his inner reverie. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘you must think these images. Readers like a man with personal integrity, morality, intelligence. They want to be able to identify with the hero, they want an identity, they want to be saved from the obscurity of having a choice. You can’t just think about love or sex, whatever it is. Think about the man after whom this street is named – Patrice Lumumba. His violent death, his desperate escape across the Congo to Stanleyville, the jubilant celebratory bonfires along the way, which made it so much easier for his pursuers to follow him, his final revolting martyrdom. Did you know that the big tree under which he died is still full of bullets?’ But he would not; he refused to think about these things. All he could think about was the smell of dried semen on his fingers, on his lips, its taste down his throat. It iced over his heart and reached down his thighs.

Freddie reached into her bag, a black bag that contained everything anyone would need for a journey. She took out a tissue and slowly wiped the tears from his face. It must be sad, this kind of leaving, she thought, especially as she knew who X was; a fraud from Johannesburg. He did not leave Johannesburg because he absconded with the church funds. He did not leave because he ran off with the senator’s husband. He did not leave because he killed a man. He is not, after all, Rick. But who is Rick in this story? And then, with a confused frown, she thought, what the hell does dried semen smell like anyway?

And as the tears continued to slide down his face, and as Freddie gently wiped them away, she realised that, even though she had created him, this unnamed protagonist, she loved him. She had wanted so badly to hold his hand on that platform – to hold him now. Instead she leant over and kissed him, not a passionate kiss, for passion is reserved only for X. X, whom he still wanted to kiss. Freddie knew, knew that only she could love him, but the lie was always in the kiss, a betrayal.

Tick, tock, tick, tock… Time is fleeting, madness takes its toll. How does the rest of the song go? And soon this story will end… Tick, tock, tick, tock… Time goes by… After time comes time…

Freddie leaned towards him as he continued to walk down the Avenida. ‘Alexandre Gustave Eiffel designed the station in Maputo, the same architect who designed the Eiffel Tower,’ Freddie said. ‘A little bit of Paris in Africa. I think he designed something in Libreville too,’ Freddie continued. ‘Eiffel was exiled from French society because he was a fraud, so he designed for the second best, the third… the fourth best. He never set foot in the places where his buildings were erected; this city, Libreville. He never left Paris. The station is the home of fraud now.’ She walked onwards. ‘I suppose Rick will always have Paris, and you, you will always have Maputo,’ Freddie said. But he did not reply. He was moody and brooding. He had just left the person he thought he was in love with, so she accepted his silence.

‘Love,’ Freddie mused, ‘that human construct. Love for a person, love for a country, love for a cause. Unrequited love, requited love that is dull enough to make a person search for another love, hope for love, the journey to find love and glory. After all, who said it? “What is the point of war without love?” The love themes can go on and on. I wonder if there’s a novel in which this theme is not present?’ She turned to him. ‘You can love X. I’ll let you love him, just for the moment, just for now.’

Now they walked into a crowded street, a more popular part of the city. A policeman, who looked like a soldier, was walking ahead of them. He suddenly stopped and looked around. He looked at his watch. Freddie wondered why time was so important to him. Did he have someone to kill at an appointed hour? Then the policeman felt in his pocket and pulled out a whistle. He blew it hard. A young man with dreadlocks in his hair and wide-angled eyes began to run. He looked wildly around him, searching for a place to hide, a doorway into which he could creep. There was nowhere. The policeman, the whistle clamped between his lips, ran towards him. There was fear on the young man’s face. His eyes were glowing, the eyes of an animal caught in headlights. The policeman took the whistle from his mouth and shouted out something in Portuguese. Maybe it was ‘halt’, maybe it was ‘what are you doing here’, but the young man did not stop running.

The sound of a shot. A gun is fired. The bullet pushes itself between the young boy’s shoulder blades. He is propelled forward by its force. He falls to the ground and lies there motionless, his blood silently pumping from his back. It is black as it mingles with the dark water of the drain into which he has fallen. A fat rat with long whiskers runs to him and nuzzles his open mouth. Above him on the wall Samora Machel looks out across the street. His radiant smile is benign. The policeman bends down over the young man. He looks in his pockets, the pockets of the tattered trousers. He pulls out some documents. Freddie, who is now close to the dead boy, leans over to look at what the policeman holds in his hands. A few pieces of dirty paper – a few pages of Frelimo propaganda.

‘Well,’ said Freddie, ‘I think they might have got the wrong man, or in this case, boy.’

The policeman got up. He shrugged his shoulders. He walked onwards. The crowd gathered around the dead boy. Someone rushed forward, also a young boy in tattered clothes. The whites of his eyes shone in anticipation. He pulled at the dead boy’s shoes. His own feet were bare. Now they had shoes to protect them. Another boy moved forward and grabbed at the bag that hands no longer grasped. A bare-breasted child, not more than ten years old, carefully took off the dead boy’s striped shirt so as not to get too much blood on it. But it was bloody anyway and had a hole in the back and the front. Better than nothing. He wanted to get as little blood on it as possible. Soon the dead youth had little left except his brown, stained underwear. No one seemed to want that, and so, with a little dignity, he was left wearing something.

Freddie was silent. He said nothing. They both just walked and looked. The silence gave Freddie time to think, about him, and X and death and history. What about society, she thought. All novels have some social element to them. Probably because people don’t live near Walden Pond, they live in a social world. And so they devise some internal drama for themselves. I must devise an internal drama. But I must also justify this internal drama; give it some validity, something that makes readers think that they are just not indulging in an individual stage show. I must create a context, a public social production: genocide, racism, poverty. It’s endless, Freddie thought, the way the same themes can be written about over and over again. And what did the reader really think of all this, these clichés? Were there enough of them to make the story moving, or were they simply laughable, she wondered. Well, she didn’t really care; after all, she would only be here for the length of this novel. Once it ended, she and this created world would no longer exist. Only the readers would continue to exist in their own worlds, worlds that they created in which to pass their own time.