Namibia – The Himba People

by Barbara on Apr.09, 2010, under Published Travel Articles

The Sunday Independent, January 2008

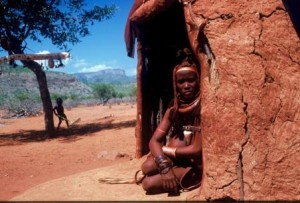

The young woman sits in the red dust, her legs are bounded by brass bangles, heavy, her spine is stretched. The squat, no longer green, Mopani tree is behind her, she does not lean against its slender trunk, it casts slight shade. From the back of the car I watch her, as she feels my stare she tucks a plastic water bottle and a burnt out cigarette butt under the woven grass mat on which she sits, out of my sight. Five tourists, including me, jump out of the white 4X4

landrover.

“Can we take photographs” a man with a German accent and shampooed blonde hair, asks the tour guide?

“Of course you can”, she says, “these are the last of the Himba people that you will find in Namibia, they are no longer what they used to be, so take photographs, they don’t mind, and, you may never get this again.”

He walks up to the Himba woman, she sits still, a fly on the wing settles on her shoulder, it moves to her outlined lips, she does not brush it away. A pair of clean khaki trousers crouches on haunches, “click, click”, a dead two dimensional image. He moves closer to her, he is almost touching her face. “I want to get her close up”, he says. The camera lens touches her staring glass eyes as he moves inwards. She smiles a painted smile.

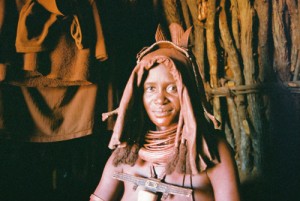

“The Himba are still an untainted people,” the tour guide tells us. “They have retained their own customs and have not been influenced by western understandings of morality or cleanliness. Look at this,” she leans forward and scratches the cheek of the Himba woman, then she takes her fingers away and shows us a red stain. “This is ochre, a kind of clay, it is mixed with rancid butter fat. She paints her face with it. It has been on her face for days.” She wrinkles her nose. “They don’t bath like we do, they have a smoke hut where they light a fire and then put herbs into it. The smoke then washes over their bodies and they get smoked clean.” She laughs, “maybe this is why they smell so bad.”

“Yes, they do smell,” another tourist says loudly. The Himba woman does not hear; a red wooden doll sits upright under a Mopani tree.

“Himbas” the tour guide continues, “are known for their pride and traditions. Everything, clothes, jewellery, and hairstyle has a meaning, they show a person’s status in the community. This woman”, she points to the young silent woman, “she has been sold as a bride. She has brass bangles around her legs. She is showing everyone that she is wealthy, but unfortunately, now owned by another. Her braid”, the guide reaches over and lifts the long coil of hair that is draped over the woman’s shoulders, “the braid shows that she is proud to be a wife. And look over there,” she points to a small grass hut from which a slender coiled whorl of smoke emerges, it is surrounded by branches of thorns, “in that hut is a sacred fire. Rituals are important in their lives. When a child dies, the family must give fire to the ancestors. They ask for forgiveness, the soul of a dead child is bad for the family.”

A crown of thorns for a dead child. A photograph validates a ritual. The Himba woman can no longer speak.

The land is barren; nothing grows from the dry hot sand. One stunted tree points upwards towards the sun, it pleads for rain, a trickle of water. A tattered piece of plastic blows across the desiccated dust, it has been torn by the parched wind from the coverings of a hut. “They put plastic on their huts these days, it keeps out any moisture”, the tour guide says. “I wish they wouldn’t, tourists want to take photographs of the huts as they really are, not with a plastic covering.”

I walk outside the rapt circle into the dust. A woman sits outside one of the reed huts. She has pendulous enormous breasts. She holds her right breast up, the nipple is elongated, irritated. She beckons to a child that is nearby; he plays with a wire car. The child says something; he sounds fractious, and walks over to her. He takes the nipple into his mouth and looks towards me. The woman caresses her other breast as he sucks and makes the motion of the camera. I shake my head. I feel a hard tearing sensation, but I cannot cry, only those with hope cry, and I have no hope that the people in the zoo that I am in will be able to break down the bars, for I to am here; I keep them imprisoned with my fascination.

The guide looks at her watch and calls to us. Five tourists climb back into the 4X4. The guide walks over to a man. He wears jeans and a sweat shirt. The logo on the shirt says ‘Running into the Future – Nike.’ She hands him some Namibian dollars. He counts them slowly before raising his head, then he nods. He shouts something out to the women around him. I do not understand what it is that he says, but it almost sounds like, ‘okay, that’s it, no more tourists today; you can get back to what you were doing.’ As we move away the woman raises her hand and waves, impurity shines from her face.

Later that evening I sit on the banks of the Kunene river, the border between Namibia and Angola, and watch a family of love birds; emerald green fluorescent light, vivid blue and black simplicity. I think about the young Himba woman as she sat in the not very much shade of the Mopani tree and wonder at this withering away of a culture, a spirit; a defeat of something inside, the defeat of a human being. I do not know these people, their land or their ways, yet I can feel the ruins of the heart. And do any of us even realise that this has happened?