Ethiopia – Harar

by Barbara on Mar.15, 2010, under Published Travel Articles

Horizons (British Airways) September 2010 (runner up winner in travel writing competition)

Selamta (Ethiopian Airways) July 2010

‘I left my life behind to catch a glimpse of life’ Arthur Rimbaud

The road to Harar is green, along the way there are lush fields, terraced farms on slopes, high growing shrubs; the road winds upwards and it winds downwards. Children dance in its middle, they paint the white line that is not there, they own it, it is their road, they wave at the car as we weave around them. “Faranji, faranji,” they call, “you want, you want …, faranji, ten birr, ten birr …yooo, yooo yooo.” They wave branches of green leaves, they sell khat, the biggest cash crop that grows in the region, fresh, delirious. My excitement grows as we move up the slopes of the mountains, organic gold, I am going to the city of a poet, the city of an outcast who gave up poetry and turned to guns, the city of Rimbaud.

Why, I wonder, am I enthralled by a city that a foreign poet lived in over one hundred years ago? Is it the city; its history, its auspicious Islamic symbolism, its mystery? I journey to somewhere foreign, an African city, but the words of another linger in my mind ‘I belong to a lesser race … the only time my race ever rose up was to pillage: like wolves on carcasses they didn’t even kill …..I am an eternal member of an inferior race …..My day is done: I’m leaving Europe…’ the city of the other, the walled city of fierce warriors, learning, coffee and poetry. Am I too leaving Europe, its brutal cultural morality, or am I entering it by another doorway, the doorway to a shrine?

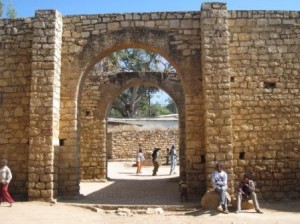

Harar is in the east of Ethiopia. It was founded somewhere between the seventh and eleventh century, depending upon what source you read, and emerged as the center of Islam in the Horn of Africa. It has a long history of capture and culture: in 1520 the city was captured by Ahmed Gragn, who, from Harar, invaded large parts of Ethiopia, then, in 1875 it was seized by the Egyptians who ruled from the city for two years, then, in 1887, the Egyptians were displaced by Menelik II who appointed Ras Makonnen, a relative of his, as its governor. It is also a propitious city, the forth holiest city of Islam after Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem, and a governmental one, the provincial capital of the largest administrative region in Ethiopia, Hararge. Separate, discrete and yet within the artificial boundary of a country; a city with its own language and, once, its own currency, a soul city.

My imagination rides the thermal wind sweep, a Nubian vulture cresting a wave, my hands shake as I feel them, smooth, unfeathered, because I have a memory of this city, I know its lore, I recreate my dreams as we approach its walls. The myth of a poet, a poet who gave up words and began to garner gold, and instead of poetic words that vibrated the senses, he wrote for the Societe de Geographic in Paris of his lonely travels, lonely as he was the only white man in the caravan, surrounded by others who he had already anticipated: the Danakil Depression, a salt desert north west of Harar, the fierce Ogaden region to the south east. Why, I wonder again, am I so captivated by a man who wrote in a letter to his sister, ‘I still get very bored. I have never known anyone who gets as bored as I do. It’s a wretched life anyway, don’t you think – no family no intellectual activity, lost among Negros who try to exploit you and make it impossible to settle business quickly? Forced to speak their gibberish, to eat their filthy food and suffer a thousand aggravations caused by their idleness, treachery and stupidity!’ He complained constantly of his surroundings, he was a deranged poet who took to commerce, selling guns, trading coffee and, as Alfred Ilg, the king of Ethiopia, Menelik II’s, Swiss adviser, the man who built the station in Dire Dawa, said, slaves. He gave up words for accounting books and numbers, he hid his gold under cushions and in faraway banks, he was no longer the hallowed Parisian ruffian who seduced a married man twenty years older than himself and ejaculated into the wine of friends for sport. Here he was an outsider, as he had predicted he would be, and he was satisfied.

Arthur Rimbaud, a different Rimbaud to that which he was in Paris, he learned Arabic and Amharic, took as a lover a high cheek boned Harari woman who did not know where he came from or what he was and became a friend of Ras Makonnen, the governor of the region. Rimbaud is not known in Harar as a poet, instead he is known as Arthur Rimbaud, the European who was not afraid to sell Hararis the guns that were used to defeat the Italians at Adwa one hundred and twelve years ago, he too did not want this paradise on an earth that has no paradise, to become a province of Europe; he did not want to break its magic for it had cast a spell over him. The Italians, powerful, with up to the date weapons, were routed by primitive spears and old Remington’s. Menelik II was so entranced by the Ras and his friendship with this strange taciturn man who complained and never smiled that this ensured that Haille Selassie, the Ras’s son, became the king after Menelik. Arthur Rimbaud and Ras Makonnen, ‘one strange couple’, cared for each other as strangers; they spoke about the town in Amharic and drank fine Harar coffee. Unfamiliar friends; different, yet similar, secretive but open, a stranger who is a friend. ‘I learnt with horror and compassion that they had been obliged to cut off your leg ….. I heard with pleasure that you are proposing to come back to Harar to resume your business. I am glad of that. Yes! Come back quickly and in good health. I am always your friend. I can feel your pain,’ Ras Makonnen wrote in a letter which he sent to Rimbaud who lay dying in Marseilles. Rimbaud never read the letter, he died before he could do so, he never did know that Ras Makonnen was his friend, his brother from outside, ‘I lent him weapons … and a second face…. Far away, good or bad; I knew I would never really become a part of his world….’ And Rimbaud never did for he died, or maybe he died for he never could have anyway?

Arthur Rimbaud, he was happy as this outsider, despite his complaints, for he had predicted it long ago, he lived it as a dream, this was his home.

Why am I intrigued, a combination of all of this, my mouth makes the words of the poetry ‘long ago, if my memory serves, life was a feast where every heart was open, where every wine flowed.’ The idea of Harar, the idea of a legend, an invention that I create as I walk its streets, smell the spices in the different market places, a Christian and a Muslim one, there is no animosity, it is just tradition that the two are separate as they sell different things. I too am the outsider intrigued by the other, detached, inside.

We drive to the gates of the city, outside are cars, rows and rows of old 1970’s Peugeots, the cars are old and French and they are blue. A man stands next to an open bonnet and peers into it, it is smoking, fumes curl upwards into the spicy air, at another a child changes a tire while a man stands next to him directing the way in which the spanner should be moved. I stand and watch time gone, a dark star that is bright but whose fire has long ago gone out.

And then we walk to the old city and touch its years with our footsteps. Inside the city I buy the best bread that I have tasted and put tomato on it, I eat my sandwich as I walk. The streets are narrow; the city is small so it is easy to walk it. Donkeys and motor scooters, Bajaj, the Indian motor scooters roar up the narrow streets, the scooters weaving and honking, the donkeys braying and stamping. Open sewers are everywhere, shit and khat and plastic bags against the walls. The walls of the city are high, in places they are broken down, in others they remain as if they had just been built, this is Harar.

We check into the Ras Hotel, a government hotel where the water does not flow, or it does, but only for short periods; the city has no water, each inhabitant is allowed three buckets a day, the water is brought in from Dire Dawa fifty six kilometres away, the pipes leak and the corridors are wide for this hotel is old. The staircase is spacious, white marble, the imagination stirs as I picture Menelik II walking downwards into the wide open area below, he is flanked by two spotted purring leopards, his jewelled fingers flash, this is now the reception and television area, young men, who do not wear jewels, stare at the football as I walk past and step onto a terrace overhung with golden flowers for a coffee, broad and expansive, the windows are framed in thick brass, it is dark and cool, I turn to look at a picture of a bird.

The walls of Harar were pierced by five gates, the number that symbolises the Five Pillars of Islam; each has its own distinctive name, and provided entry to trade caravans travelling to and from different stretches of the surrounding country. Richard Burton entered into the eastern gate, he came to the city for ten days, the Timbuktu of East Africa, the centre of learning and culture, no foreigners were allowed for they brought with them ill luck and bad fortune, and so he disguised himself in the clothes of an Harari and entered the city. Nameless he wrote First Footsteps, a foreign account of the city, its people and its hyenas.

The streets are uneven, cobbled, the sun is hot, there are few shadows. The wall of a building casts a small amount of shade onto the street, a man lies in this shade, he smiles, he has few teeth, next to him is a branch of green leaves, his mouth bulges it is as if he has a ball in its side, his lips move as he masticates, he smiles again. Khat, the leaves that create euphoria and then mellowness, high energy, aggression then a tranquil sweetness. An old grey man lies in the shade, his morning assertions are over, and so he chews, a young boy hovers near to me and asserts his right to sell fine frankincense and he chews, a prophet preaches an epiphany and he chews … ‘The poet makes himself a seer by an immense, long deliberate derangement of the senses’. The city is filled with poets, khat chewing khat sellers line the streets and offer you bitter leaves, the plant that throws the senses into disarray, make you a poet, a seer. The chemicals in khat are in the same class of chemical as amphetamines, when the khat leaves are chewed, cathine and cathinone are released and absorbed through the mucous membranes of the mouth and the lining of the stomach. The actions of these chemicals cause the body’s neurotransmitters, or receptors, to absorb more serotonin, resulting in wakefulness, euphoria, and then serenity; the effects are similar to those of cocaine. Harar, a city of narcotic lethargy.

In the evening we take a taxi to the outskirts of the city, here the man that feeds the hyenas meat from his own mouth puts on a nightly show. Harar is known for its hyena’s, the garbage removal system has never been renowned for its efficiency and so the hyenas prowl the streets at night watching and waiting for maybe, just maybe a human form, but if not, for the waste that has been thrown out during the day. Harari’s do not go out at night, they fear the bandit hyena, I hear its call as I lie half breathing in the Ras Hotel at night, strange and eerie, a wild shaggy beast in a city. The hyena feeding man, wears a t-shirt that smilingly says ‘Toronto’, he smiles a showman’s smile and, for a fee, he puts on an astonishing performance. We turn on the head lights of the car, he is illuminated, the eyes of the beasts circle him. In his hands he clasps a reed basket from which he takes bloody meat, camel meat, the excess fat seeps white between his fingers. He puts this mixture of fat and blood on a short stick, he holds the stick in his mouth, the beasts circle him, they make strange sounds, then one comes close, closer and takes it, he holds his arms in the air and waves at the small crowd, his face smiles as if from a Hollywood billboard. Again and again he does this, I gasp each time the muzzle of a hyena comes close to his face, their jaws are strong and can crush a man’s hand in a bite, his face is scarred, his performance is fearful, it makes me breath faster.

The following day we walk to the Rimbaud Centre, a house that was not in fact the house that Rimbaud stayed in but the house of an Indian trader which has been restored and is now a museum dedicated to this renegade poet. I go inside and look around me; there is a staircase that goes upstairs. Downstairs there are two rooms; in one are the books of the celebrated poet, ‘Une Saison de Enfer,’ his geographical writings, books and books, poetry and accounts. In the next room are photographs, a lonely prophet in white stares at the camera, obsolete, a self portrait, the famous picture of a coffee merchant, the Harar houses and streets. A photograph is a lonely place, I think as I look at the face of Arthur Rimbaud, it watches me as I bow my head; the cold blue eyes stare, delicate features, unbearably sad, calm, an unimpeachable expression, childish lips that never smile and the slight lift of an eyebrow. I know the stare; it has always looked past me. The blue eyes focus on something outside of me, outside of this city, outside. Photographs are lonely, no-one inhabits them; they have no smell, they do not breathe. Upstairs I stand at the window and look out at a city, a walled city, the same city that Arthur Rimbaud looked at one hundred years ago; rooftops and ravens, people that walk, children that sing.

I walk outside this house that was not his and talk to the curator of the Centre.

“Ah Arthur Rimbaud, he does not have a good reputation in Europe, fire power he brought with him, but I say that he brought fire power and helped us send the invaders away. I have read books about Arthur Rimbaud, we are pleased that he came here, we are very pleased,” he smiles and offers me a khat leaf to chew. “He came on the same day that Richard Burton did, they entered the same gate, only he came many years later, Richard Burton, he stayed for ten days, Arthur Rimbaud, he stayed for ten years. This is not his house, I think his house is closer to the market place, some say he lived on the main square near the west gate, a small two story building that is now a bar. We do not drink in Harar, we are Muslims, but in there, there are drunk people. But I do not think that this was his house, maybe it was for a short while, but I think he stayed two houses from here.”

He gets up and points up the road, “there, in that house that is falling down, I think that he lived there, downstairs is a place where he could keep his goods, upstairs, the place that he slept in with his wife, a Harar woman. He loved her very much you know; there is a photograph of her in the museum.”

The curator does not know of the poetry of Arthur Rimbaud, he just knows its words, he bows his head, as I do, as he speaks of this man for he too has made a laurel wreath and placed it on his head, he has invented a fable.

Arthur Rimbaud, he was happy here, lazily and defiantly anti where he had come from, it was nothing like his home, ‘a drunken boat’, the star that summoned him to the ‘season in hell’; after all hell is just the place where the other resides, for a season.