Namib Desert, Namibia

by Barbara on Jun.05, 2009, under Published Travel Articles

The Sunday Times, August 2005

The small four seater Cessna 182 lazes in the hanger, it is white. The letters ‘AFC’ are painted in blue along its side, ‘Alfa Foxtrot Charlie’, a pretty name for a pretty plane. We push the plane outside into the cold Johannesburg air and climb in. ‘Oil Pressure – Green, Alternator – Positive Charge, Suction – Above Zero, Set Compass, Radios on …’ We taxi down the runway and climb the air.

I am enclosed in a bubble of steel and wind, and yet there is no feeling of being inside, I am above the earth. I am awake and exhilarated, I am open in this closed in space. Up we move and eventually settle at 9500 feet. At this level we cruise. From the sky I look down at the world. A world that I know, and yet from here I do not know it. I am not on the earth, but yet the earth is here, it is tangible, it is close. And because I am looking downwards, me to the earth, horizontal rather than vertical, no longer on the same level, I reinterpret it, ethereal, elusive, a photograph. I think of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s words in ‘Wind Sand and Stars’, ‘A person taking off from the ground elevates himself above the trivialities of life into a new understanding.’ A picture from height is close to god-like.

At Keetmanshoop, we put in fuel and clear the Namibian customs. A soldier with a wide mouth that smiles bright white teeth stands on the landing strip next to the plane and talks to us. ‘Where are you from,’ he says, ‘what nationality are you, where are you going to?’ His lips are dry and cracked from the hard wind that blows across the wide highway of the runway, but this does not mar his smile. He does not need a billboard smooth lip cared for mouth to be beautiful. ‘Do you like Namibia?’

‘I like it,’ I say. I feel as if I could grow old in this harshness.

As we fly over the red sand dunes I talk to god. Underneath us the mountains are flat, and yet they rise into the horizon. The dirt roads that pierce the desert sand stand out like scarred skin, puckered. Here and there is a small dwelling, a stitch on the skin, a scab, and sometimes there is a tree. All around there is nothing. We search for the Aandaster landing strip. For a long time we search, flying low over ochre sand and a herd of gemsbok, so low that their horns almost touch me. And then it is there, a line of white stones and a herd of springbok that graze desultory next to them; a wind sock hangs its head like a shy young girl; she welcomes us to the ground.

We are two hundred and fifty kilometres to the south west of Windhoek, and one hundred kilometres south of Sossus Vlei, in the middle of the Namib Desert. The place where we are to stay borders on the Namarand Nature Reserve, a nature reserve, closed to all except those who own it. The farm was bought from a farming family. They used to farm cattle and sheep, but life became too arduous for them. Cattle and sheep need more than 60 millimetres of rainfall a year to survive. And in these times of money and conservation they were forced to sell. So they sold their farm and kept a small piece of earth where they built a lodge. The lodge is small, the food is farmer food. There are hard beds in the bedrooms and the electricity is generated by six large solar panels which have to be constantly turned during the day to catch the sun. I fell like a traveller not a tourist. This is my home. I feel part of the desert sky. When I sit down to potato and boiled vegetables, I hear the bitterness in the farmer’s voice as he asks me whether I enjoy the food. I know that the land acquired by colonialists was by force and violence, and yet still I can hear that he has lost, how ever the land came to him, it still became a part of him. And now he is part of the service industry; he cannot feel the sand on his bare feet, he does not know the horns of the ram that has been with from the time that it entered the world to the time that it went to the slaughter house. I sit on the balcony of my room; there are no chairs, just concrete. I sit and watch the lonely pale chanting goshawk circle the one red flower of the aloe bush in front of me; he is searching for a mouse, or a cricket, supper. There is no place to hide. I sit and watch the yellow desert sand. The sun leans forward sucking up the day, orange, sacred. I feel warm as the earth darkens.

Nature writing is a cliché, it is worn-out. It is trite to write about nature nowadays. Nature writing is scorned by those who know things that are significant, vital, imperative. A reviewer of the poetry of Pound once wrote, ‘After the war, the allies kept Ezra Pound in an open cage in the sun for a year, because he had committed treason by supporting fascism. He was able to observe nature closely during this time, since there isn’t really a lot to do in an exposed cage, and was able to use his observations later when he wrote the nature section of the Cantos.’ So much for Pound and poetry and nature.

And the other side. Nature writing is revered by those who know things that are significant, vital, imperative. Nature cleanses and purifies. It is pristine, ancient, it reaches into man’s soul and restores the link that has been lost with someone higher, who ever this god is man finds grace in nature, it allows an experience of the spiritual. Raymond Carver left the seedy semen stained sheets of the motels in the mid west that line Highway 54, he left the smeared red lips of the bar room girls who wait for love, he left it all for the world of nature. They say his writing electrified. And then he died of alcohol poisoning knowing that there was something else besides the illusion.

And other writers, those that know that it is official that damage to the environment has reached a point where it can never be reversed no matter how many Kyoto Treaties are signed, or not signed, as the case may be, consider nature writing as urgent. It is the future, an illusion, pastoral, inevitable. The cool and the creepy and the vibrant. It opens a space in the performance, the variety show, the theme park. Nature is pre packed into words, into trendy tourist destinations, it is a commodity, to be bought and sold, with all its vibrant mythology. It is an experience for those who have never touched soil, for they have a paved in garden and a garden man who comes twice a month to water the burnt out shrubs in the three millimeter flower bed that lines the razor wired property wall.

But for all the cliché I can only do nature writing when I think of the desert. I have to do purification, punishment, regeneration, performance. The desert overspreads all of this, a finely embroidered quilt, and yet there is no quilt, there never was one, so it can never cover anything.

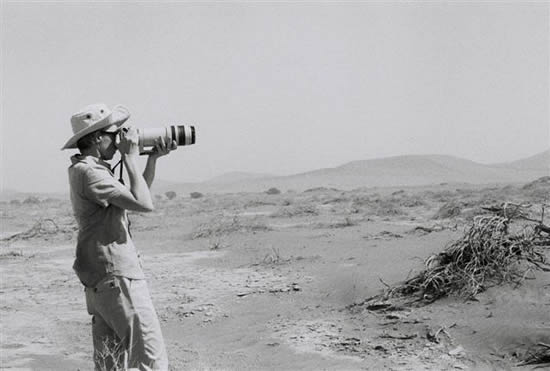

There are no emotions in the desert. There is the sky that is blue, and when I put a polarizing lens in my camera I can make it bluer, cerulean, cobalt, azure. I try to make it more than just bright blue; I try to find more words. There is red sand, that if I choose, I can make it redder, or I make it washed out and pale, under exposed. I make the variety show. The desert is empty. I am empty. The wind whips around my body and rips the skin from my spine, a filleted back bone, naked. There is no place to hide as I can hide in a city. There is no happiness that I can buy or designer depression to cover me. It is the extreme of nothingness. And yet as I write the word ‘nothing’ I sound pejorative, bleak. The positive value of loss is always articulated as a gain, a martyr, here I can write no gain, for there is nothing, empty, complete. Words are the generators and bearers of an idea. And if there are no adequate words then can there be any ideas?

The desert with its nothingness creates dreams that cannot be articulated. The desert is superb, beautiful, nothing, magnificent…. Everywhere there is sand. High red gold dunes that stretch upwards and engulf the sky. Stunted, blackened skeleton trees in a Sossus Vlei sand storm, the sand spinning in the wind makes the air purple and hazy, Orpheus wanders in this underworld and dances with the dead, but he is too afraid not to turn back. Touches of yellowed green grass, a lonely piece of life grows up from the fine red, a white flower emerges out of the green only to be decollated by the wind. A hard backed dung beetle, or a poison tailed scorpion, tracks its way up a slope, where does it go? A gemsbok print, feeling tired dragging a back leg, maybe injured or thirsty, trails behind the fine insect line. A foot print marks the dune 45, the only sign of a human. A single sign post points the way to the Dead Vlei. And I can not speak or write anything as there is nothing. There are no words that can convey this. Full equal’s positive, empty equals negative, and yet here it is full of emptiness. No water. No clouds. And as I sit in a vacuous daze the words of another who wrote in the desert come to me, ‘the sheltering sky remained overhead. And behind the sky was blackness, the erotic, interminable, relentless sky’. Emptiness creates passion.